Trumpeter 1/32 F-105D Part 1

By Dr Menelaos Skourtopoulos

Dropping The Doumer Bridge Building Trumpeters F-105D in 1:32 scale - Part 1

by Menelaos Skourtopoulos & LtCol John Piowaty (USAF Ret)

Introduction

The Republic F-105 Thunderchief of Vietnam fame needs no introduction. It was simply the best single-engine, single-seat fighter bomber built. It could do its job better than any other aircraft of its time, and could kill MiGs too.

This article and my model are dedicated to the pilots and ground crews of the "Thud" in Southeast Asia.

A Memorable Mission

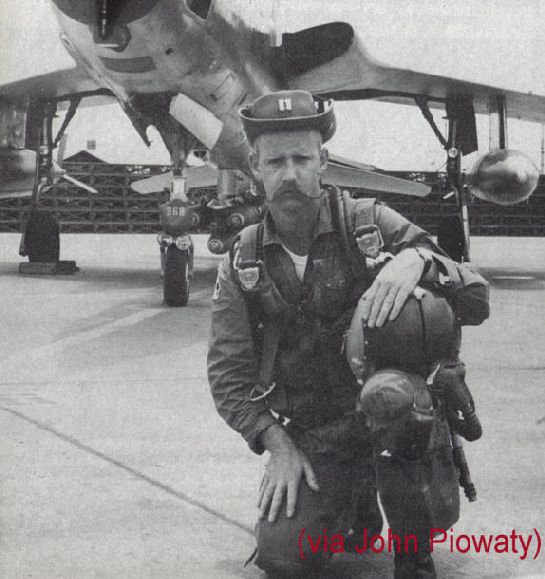

LtCol John Piowaty is one of the men who flew 100 missions over North Vietnam. His most memorable mission was on August 11, 1967, flying with the 355th TFW, 354th TFS out of Takhli RTAFB in Thailand. His narrative follows:

On the morning of August 11, 1967, we were planning the afternoon mission when a staff sergeant stepped to the target board. With a yellow grease pencil he lined out the primary target data and wrote in a new target number, '12:00.'

"What's that?"

"The colon means it's one from the JCS (Joint Chiefs of Staff) list."

"I think it's that big bridge heading into Hanoi."

"Oh, crap!"

"Hey! You're the one who was bitching about one-pampers (easy targets) at breakfast!"

"Yeah. But that was at breakfast!"

Under Target Name the sergeant wrote, "Paul Doumer RR & Hwy Br."

"That's it, the big bridge!"

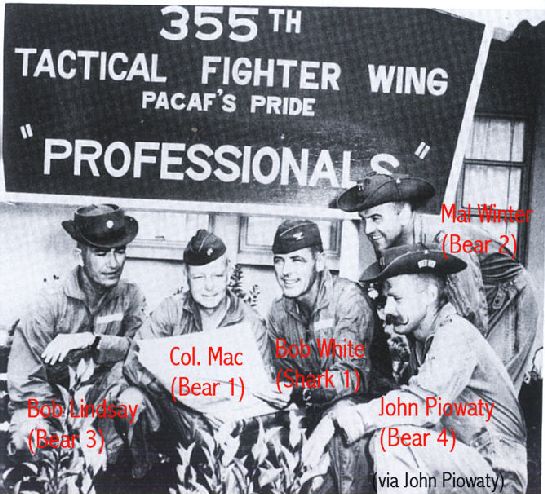

Then more grease pencil. We got a new force commander and new flight leads. Colonel Bob White of X-15 fame was going to lead with Shark Flight. Bear Lead was my squadron commander, LtCol Nelson MacDonald, generally known as Colonel Mac. I got moved to Four, Mal Winter became Two, and Bob Lindsey was Three. Subsequent flights were to be led by other squadron commanders.

They slipped the takeoff time one hour to give the guys on the ground time to change the ordnance loads on the planes. I have to really give the guys credit. With the one hour slip they downloaded the six 750-pound bombs on the centerline MER. They also downloaded the 450-gallon wing tanks. Because the wing pylon wiring was specific to the load, they had to remove the wing pylons and upload new pylons, then load 3,000-pound bombs on the wing stations. The centerline bomb rack was replaced with a 600-gallon belly tank. To get all this done in one hour, they bent some rules. They downloaded the six seven-fifties all at once…with the MER, fuses, and all! In order to do this they had to put two or three guys on the back end of the MJ-1 bomb loader to keep it from tipping on its nose. They violated the rules by downloading full fuel tanks, but they did it without spilling a drop of JP-4. Every plane got loaded out, every plane started on time and took off on time.

While the loading was in progress the flight crews headed into the briefing room. Time over target (TOT) was 1600. There were 20 Thuds in four flights, plus two airborne spares and three ground spares. One flight comprised four F-105Fs, the two-seat "Wild Weasels." First came the time hack, then intel:

"Extremely heavy flak of all calibers through 100 mm. SAM sites 22, 18, 97, 35, etc. are active. MiGs will be up from Kep Phuc Ken, Yen Bai, Gia Lam, and Hoa Loc airfields. Target winds are 350 at 8."

Colonel White took the stage, looking not unlike Gregory Peck in Twelve O'clock High, to give us his overview of the attack. We'd make the usual run down Thud Ridge. Colonel White's Shark Flight would move out ahead a few miles to drop CBUs as flak suppression. We'd have a right hand roll-in to bomb, and a left egress down the Red River, then turn right across the flats to the south. Our tankers would meet us on egress at Orange Anchor.

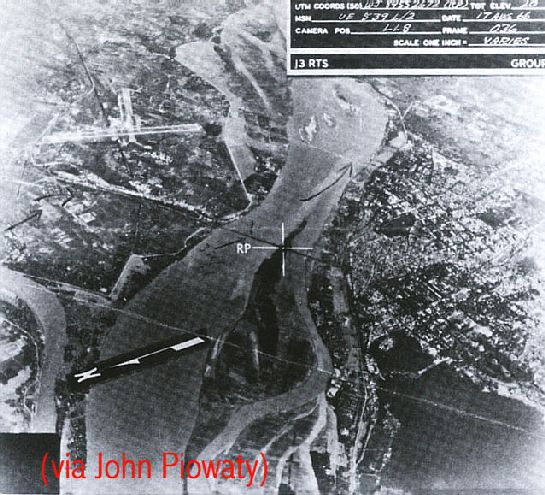

I had an aerial photo of the bridge which had been taken from about the same position we would begin our target run. I repeatedly held the photo, turning it to represent the view I'd have when rolling in, then drew it closer to my face to get the view I'd have at bomb release. I later folded the picture and tucked it over the face of my radar scope in the plane to study it as we flew north.

We went to have lunch at the Officers Club. The target and associated danger seemed far away . . . until I realized one of my flight mates was humming Downtown, the Petula Clark chart leader of that month. "Shhh!" he was chided.

At the squadron equipment room I suited up with G-suit, life preserver, survival vest, .38 revolver, parachute, helmet and mask. Sixty pounds heavier, I waddled out to the crew van with the rest of Bear Flight for the ride to our respective jets. I preflighted 415, the Thud I had drawn (my personally assigned plane was 234, SORRY'BOUT THAT!) like a cowpoke walking around his horse--a pat here, a slap there--then climbed into the cockpit and strapped in. The crew chief checked me over, climbed down, and pulled the ladder away. I pushed the mic button:

"How do you read, Chief?"

"Loud and clear."

"Starting in one minute. Taxiing as Number Four."

"Got it."

"OK. Ten seconds. Clear to start?"

"Clear."

There was a belch and a whooshing sound, the hum of the turbine winding up. The crew chief responded to my calls to check flaps, speed brakes, furl tanks, pitot heat, and gun purge. Then we waited.

"Bear Flight, check!"

We responded in sharp cadence, "Two", "Three", "Four", "Spare."

"Takhli Ground, Bear taxi five."

We taxied to the arming area where a group of mechanics and bomb loaders made last minute checks of each plane and pulled safety pins and streamers. Then we passed "thumbs up" to Colonel Mac. He called, "Takhli Tower, Bear number one with four."

"Bear, winds one-five zero at six, cleared for takeoff."

We pulled past Spare and onto the runway. Each sighted over the planes to his left to line up perfectly. Colonel Mac spun his right index finger for run up. Two and Three passed the signal and four Thuds' noses dropped as their tailpipes spewed thousands of pounds of thrusting, hot exhaust. Engine instruments OK. We passed "thumbs up" back to Colonel Mac and he was rolling. Then Two, twenty seconds later. Then Three, and finally my turn. One more scan . . . Nineteen, twenty seconds, and I was rolling! The afterburner kicked in . . . BOOM! I toggled the water injection. Speed built. Back on the stick at 183 and airborne at 193. Gear up; flaps up. I called. "Bear Four, airborne."

I turned for cut-off and accelerated to 400 knots. I gently moved my Thud up to and alongside Bob Lindsey as he pulled up on Colonel Mac's left wing. I zig-zagged a few degrees to slow down, matching 350 knots.

Two hundred miles north we met the tankers. Colonel Mac went directly under the tanker and took his gas. I moved in after Mal and refueled in a sterile, silent, mechanical coupling with a smooth-skinned, oversized mate!

We moved to the north, holding 350 knots. The Weasels moved out ahead to clear the way from SAMs and gun radars. As we approached the Red River, Colonel White pushed our groundspeed to 520 knots, and at the river accelerated further to 540. As we approached the target area it seemed every gun there opened up. The previously blue sky clouded up with gray and black bursts as we made our last turn toward the bridge.

Suddenly Colonel Mac's Thud was belly up, then gone--pulled down with four or five G's; then Two, then Three, my turn! I lit the burner as Three rolled inverted. I rolled quickly behind him, at fitrst with no G-s. Then I pulled my nose down, below my aim point.

The wind was from 350 degrees at eight knots, and I had computed my aim point at sixty feet from the span I was briefed to hit. When you're after a target as big as a mile-long bridge, 38 feet wide, it's not easy to make yourself aim at a patch of muddy water sixty feet away, but I knew I had to aim there. I'd drawn an arrow to that aim point on the photo I carried, and I'd fixed my mind on that spot in the water.

We overshot our roll-in just a little, so as I rolled in I was forced to adjust back from left to right. I started down the chute, put the pipper on the aim point and pickled off my bombs. I'd done my work. Gravity took over the flight of the bombs, and I was on my way out of there.

I pulled off kind of easy. I didn't like the seven G pullouts, since they caused gray vapor to cover the plane, obscuring the windscreen and making the plane easier for the gunners to track. I liked to limit my pullouts to four or five Gs. I came out 500 to 700 feet lower, but I had 50 knots more airspeed to use in my escape. On my pull-off I swung a bit to the right. I wasn't in a hurry to head downstream to the joinup point seven miles away. I had marked my photo with the location of the POW camps and decided to let the guys know we were there. I went down to 4,000 feet over the town. I had no idea how loud we were with bombs and afterburner, but I wanted to make sure they heard that somebody cared.

I pulled hard left and headed downstream, indicating 630 knots as I looked for my flight.

All of a sudden, I started seeing things the size of Beaujolais wine bottles streaking by the cockpit with about a 50 know overtake--85s! Radar directed, heavy AA fire! I was several miles from downtown Hanoi and feeling invincible, invisible. I was just starting to lay my Thud into a right turn to join on Colonel Mac and suddenly, an explosion! The horizon disappeared as the tail of my Thud was blown up and to the left and the nose was pointed down at the carped of rice paddies below!

The instrument panel filled with warning lights and the instruments went crazy for a few seconds as the plane fish-tailed back and forth. The lights showed a fire and utility hydraulic pressure loss. I cut off the air turbine motor that pumped utility hydraulic fluid back to the speed brake and engine nozzle area--a likely place for a fire.

Mal Winter, Bear Two just then called, "Three, you're hit!"

"Oh, no!" I thought. "Three's hit, I'm Four, and I'm hit."

Then from Bear Lead, "Two, you're hit!"

"My God! Two, Three, and Four hit!"

Then Mal came up. "Two's not hit, but Four, you're hit. You're on fire and you're torching a mile."

I answered with the coolest "Rog." that I could muster. I'd lost my flight instruments but had a standby airspeed instrument the size of a quarter. It went only to 400 knots and it was pegged. I got a clue that I was going plenty fast when I got a call from Colonel Mac, "Damn it all, Bear Four! If you'd slow down, maybe we could catch up and give you some help!"

I throttled back and started an easy climb to 12,000 feet. I should have slowed more, because too many pilots had snapped legs in high speed ejections when their planes went out of control due to hydraulic loss.

We headed to Udorn, just south of the Lao-Thai border. Colonel Mac stayed on my wing as I slowed to 250 knots. OI dropped the gear and flaps and brought my speed down toward a calculated final approach of 190 knots. Since I'd been told that the "peanut gauge" was accurate to only plus or minus 30 knots, I gave Colonel Mac a call, "Lead, how's my speed?"

"Doing fine. No sweat."

So I held my speed where it was, coming down final at 205 and flattening out over the dirt overrun. She stopped flying and hit pretty hard. I reached for the drag chute handle and pulled. The rescue chopper pilot called, "No chute, no chute!" I was rolling along at over 200 miles per hour! I had no hydraulic pressure for brakes or steering. I Pulled the handle that loaded 3,000 pounds of air pressure into the brake cylinders and slid my feet up on the pedals and blew out the right tire! I used all the left rudder available to keep straight and gingerly pressed down on the left brake pedal. The mid-field barrier, a steel cable over an inch in diameter was coming up fast. I flipped the arresting hook switch to EXTEND. The nose wheel bumped over the cable, the bird slewed a bit more to the right, and I was stopped.

I shut down the engine and checked the clock: 1746. I'd log 3.5 hours, mission symbol 1.1, combat over North Vietnam.

After I climbed down, I walked around 415, amazed at the damage. My two primary hydraulic lines to the tail were scarred by the shrapnel. A little deeper and I would have been in a rice paddy southeast of Hanoi with broken legs. What a tough machine!

I got a beer at the 13th TFS at Udorn and caught a hop on a C-47 Gooney Bird back to Takhli. I put another mark on my "Go to Hell" bush hat. Fifty-five missions done, Forty-five to go. When I walked into the Takhli O'Club, my buddy Mo Baker, who was behind me on the bomb run in Scotch Flight, met me with hugs and back slaps. I'd put a 3,000-pounder on my assigned span. The Doumer Bridge was down.

Menelaos Skourtopoulos & LtCol John Piowaty (USAF Ret) 2004

This article was published on Wednesday, July 20 2011; Last modified on Saturday, May 14 2016